And the other day, in the midst of running hither and yon to get a new back window put in my car (smashed it myself, by accident of course, closing it on a boot full of wood) I came up with a whole new book idea. Not that I’ve anything like finished the novel I am working on. The new idea would involve using some of the stories I am writing at the moment. No, not exactly a short story collection. More in a later post, when I have the idea better worked out.

I am managing to put some serious time into the current novel. It’s a matter of editing and rewriting at the moment. I like the story, it’s the writing that needs work!

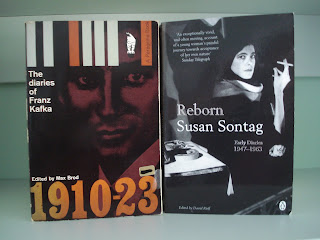

I read the first volume of Susan Sontag’s letters, called Reborn and edited by her son, David Rieff. I can’t say anything about it because it’s my book club choice and some of my book club people read this blog. After we’ve had our book club discussion I’ll say more about this book.

Stimulated by SS, I found Kafka’s diaries in a second-hand bookshop and have just started reading those. (I recently read Metamorphosis because my son mentioned it as an important book to him when he was young but grown-up.) I don’t have a handle on Kafka at all, but am already riveted by his diaries. He is, to put it mildiy, a miserable fellow. Sometimes it hard to tell whether a diary entry is just that, or an attempt at something he wants to write. His lack of belief in himself and his writing is well expressed in this sentence: “My doubts stand in a circle around every word.”

Here are two of my short stories: (I’ve included the first one because Prue liked it.)

Separations

When you have parents who don’t get on, and you are an only child, you learn some things. Angela learnt that she could often get what she wanted by playing them off against each other. The down side of that was that she never felt she could quite trust the stability of the situation. Her parents didn’t row, or at least not noisily, and they slept in the same bed, so it wasn’t embarrassing when her friends came over after school.

The worst thing was hard to describe; a kind of tension. It would vanish when she and one parent were together, cooking something, or watching television, or doing her homework, but when the other parent came into the room the air would turn cold and empty-feeling and she would know she had to be careful to not seem to favour one over the other, to spread herself evenly between them.

When her father told her he was leaving, he assumed she would stay with her mother and visit him on weekends; he’d get a flat not too far away, he said, so she could still see her friends. Having separated parents wasn’t anything unusual, but still, she was anxious. I’m thirteen, she wanted to say, I’m the one who’s supposed to change things, you’re the grownups you’re supposed to stay the same until, well, at least until I finish school.

They both went to a lot of trouble to tell her that it wasn’t her fault, she hadn’t done anything wrong. She knew that and she knew that parents always say that, she had known it since Valerie’s parents separated when she and Valerie were six, and there had been plenty of break-ups since then.

Once the separation actually happened, Angela noticed her father fading, gradually getting more and more hazy, seeing her less and less often, paying her less attention when they were together; something about having a new wife and baby. She didn’t mind, the new wife was a terrible fusspot, more concerned about her own makeup and clothes and that people might think Angela was her daughter, and that she was old enough to be mother to a teenager. When Angela got to university and struck Gertrude Stein in third year English Literature, she found an explanation of what happened with her and her father. “Little by little we never met again.” They did see each other occasionally, but they never met in any real sense, they never said more to each other than pleasant nothings. “How are you?” “Fine, thanks. And you?” “Oh, good.”

Being just Angela and her mother in the house was surprisingly relaxed and easy. There was the occasional man who stayed over, but never anything serious, and Angela herself even had boyfriends stay over once she was sixteen and that was never a big deal. Then Angela went off to university in Wellington and her mother sold the Wanganui house and moved to Otaki to live with a man who bred llamas.

Angela completed her first degree the same month that her boyfriend and her best friend broke her heart. Julie, her second-best friend took her off to spend the summer in midst of her own seven-sibling family. With partners, sundry extras like Angela, and children, there were nineteen people in and around the rambling house. Tents on the lawn. Bunks in the sleep-out. Julie and Angela shared a built-in veranda that had two single beds, end to end.

Christmas and New Year were a kind of family chaos that Angela had never known. No solitude. No silence. No pressure to do or be anything in particular, along with an expectation that everyone would lend a hand here and there while Julie’s mother orchestrated the whole. And everyone was responsible for their own stuff. “Leave it lying around and lose it,” Julie advised. “Leave it in your bag or on your bed and no-one will touch it.”

It didn’t take Angela long to notice cracks, jealousies, manipulations. They fascinated her. No-one, certainly not Julie, wanted to talk about any of that, it was like a river, all action and doing on the surface, surging sometimes, quietly pooling some-times, but with undercurrents pulling this way and that, unexpected eddies and blockages making confused and confusing ripples and waves, some of them powerful, none acknowledged.

One of the older brothers, Alan, was taken with her, Angela could tell. When he was around she stayed closed to Jill, mother-organiser.

In the first week of January, when Angela was beginning to think about extracting herself back into her own life, which she could at least bear to think about again, one of the children drowned in the river. The real river, the one flowing past the bottom of the long garden. Kevin was six, one of the kids that ran about all day doing kid-stuff, being hushed regularly by the adults.

Some wanted to know what happened, wanted to blame someone, a parent, an older child, someone. Others went quiet, comforting and being comforted. Two brothers dealt with the police. A sister-in-law and Julie dealt with the media. People swore and cried and went for walks in ones and twos and the departures started. Irritations and squabbles came to the surface. Angela left with the first wave, deciding for herself that her bed was more use to the family than her presence.

She stood in the bow of the ferry as it ploughed through Cook Strait, feeling the wind against her body, the spray not quite reaching her, and thought of her ex-boyfriend and her once friend together and saw that the hole in her life was quite a small hole and diminishing.

Home and Away

Time to go home. She thinks she knows where home is, and it’s not where her heart is, her heart is a tired, dry, shrivelled thing inside her. Home is that familiar place, that place where she can stand and know where thing are; Australia is that way, across the Tasman Sea, for South America she will need to turn east, towards the Pacific Ocean, south is Antarctica (yes, yes, Antarctica is always south). Almost everything else is north of where she stands when she is home. At night, looking up, she will be able to find the southern cross and work out half a dozen other star forms in relation to it. She knows the weather, whatever it is, will change, that there are spaces of countryside between cities and towns, that home is small and underpopulated except around its northern city, and both future-focused and backward-looking. Sooner or later she will run into people she knows, there will be friends who have drifted and friends who will fit right back into her life and she theirs.

She will go home and wear it like an old, comfortable coat, and rest. It will not be the rest that lasts until death, it will be rest to fit her for the restlessness that is just as familiar as home, the restlessness that will drive her on. This she knows, as well as she knows that for now her only option is to rest.

The volume of noise sinks. The helicopter has landed.

I like both stories - the first is easier to get in to, I think (for me, anyway), in spite of the second being so short: that makes it demand more of the reader, somehow.

ReplyDeleteAlso want to note how impressed I am with the constant writing. I know you enjoy it, but even so, the discipline & focus requires a lot of effort!